The Letter

Morandi Wrote to Thelonious Monk

Introduction

While doing research for my last project, The Light of Memory (August, 2021), which pays hommage to the great Italian painter, Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), I came across a reference to a letter he had written to the great American jazz composer and pianist Thelonious Monk (1917-1982). The letter expressed his heartfelt appreciation for the music he had heard at a concert in Milan the evening of April 21, 1961. Morandi had never before heard Monk's music, and I had never before heard of this letter. I really wanted to learn as much as possible about the letter--why Morandi wrote it, and if possible what he said in the letter--for I have been a fan of Monk's music since the 1980's and I was excited by the idea that Morandi, one of my most favorite visual artists, appreciated Monk's music so much that he would write a letter to the world famous musician.

Between 1994-2000 I made a large series of miniature photographs inspired by brief pieces of piano music. I entitled the project, which consisted of nearly a thousand 3.5" x 3.5" silver gelatin prints, Studies I. Eleven years later, while I was making a digital (blog) version of the project and listening to the music of Thelonious Monk, I realized that despite my love of his music I had never mentioned Monk as an influence on the Studies I project. Monk's Quirky Music, the second numbered Studies project, created in 2011, was my first hommage to the great jazz composer and pianist.

This present project is my second tribute to Monk, and my third to Morandi, in remembrance of their crossing of paths on April 21, 1961 when Monk performed in a concert in Milan. The music was something like an epiphany to Morandi, and he was so inspired by the revelations of his experience that he wrote a letter to Monk to explain what had happened and to express his gratitude.

*

I first learned of Morandi's letter to Monk in late June, 2021 while reading Marilena Pasquali's 2019 book Giorgio Morandi : The Feeling of Things. She had included an essay, written by Tullio Pericoli, in which the author mentioned that Monk had traveled to Milan in April, 1961 on a business trip and while staying a few days with a friend there was invited to attend a jazz concert featuring Thelonious Monk. Morandi accepted his friend's invitation though apparently he had never before heard of Thelonious Monk.

The day after the concert, on his way back home to Bologna, Morandi wrote a letter to Monk which was discovered by Favio De Marco, an artist and bibliophile, as he was rummaging through Morandi's old papers some time after Morandi's death.

(Note: I don't know if Morandi's letter was ever actually sent to Monk. I do know the April 21, 1961 concert was recorded live and made available on the Riverside label in 1963. It remains available today under the title Thelonious Monk In Italy.)

Pericoli's brief mention of the letter focused only on a comment Morandi had made regarding the way Monk played the piano with his fingers held very stiff, "like drumsticks." I wanted to learn more about what Morandi had written in his letter, so I began a search on the internet to see if there was more information available about the letter. I found two useful links.

In an Art International review of the 2019 retrospective exhibition of Morandi's work at the Guggenhiem Museum in Bilbao, Spain, the reviewer Allie Biswas mentioned Morandi's letter:

An anecdote relayed by the exhibition’s curator . . . prompts a reconsideration of Morandi’s motives. In April 1961, the artist went to see Thelonious Monk perform in Milan. The legendary jazz pianist, known for a unique style that helped to shape modern jazz, proved to be a revelation. Traveling back to Bologna the next day, Morandi wrote a letter to Monk. “Last night, I obtained a lot of answers from you,” he declared. It is a shame this encounter took place three years before Morandi died. ( click here to see the complete article)

When I read this brief, cryptic reference to Morandi's letter I felt all the more determined to learn more about the letter. I wrote emails to curators and scholars and searched the internet further. At last I came upon a link, in Italian, which included Morandi's letter. Since I cannot read Italian I opted to view the rough English translation offered by Google: http://senzadedica.blogspot.com/2016/04/il-pittore-e-il-musicista-giorgio.html

I am offering below an English translation of Morandi's letter that I have edited and made additions to based on the Google translation in the link above. It is my attempt at trying to "translate" the Google English version of the letter into a version that makes the most sense to me. (I would love to see other English translations of the letter especially by individuals who know the Italian language well, who know Morandi and his work well, and who know and appreciates Monk's music.)

April 22, 1961

Mr. Monk, despite my limited knowledge of your kind of music, I was struck by its musical timbre, so precise and disjointed at the same time, capable of generating a melody that recalls the solid and granite shapes of the rocks of my Apennines. I sat quite close to the stage, and I still have imprinted in my memory the movement of your fingers outstretched like drumsticks on the keyboard which sculpted the rhythm of your music with a surprising economy of notes.

The reasons for this letter come from some recent questions I have had about my painting, to which your music, in ways unknown to me, seems to have answered.

Artistic research always generates questions to which, in some cases, only art itself can give an answer, and sometimes the answers come in a form outside of one's own familiar language, such as the music I heard you perform yesterday, an the answer which came from your artistic expression which possesses a strength that transcends differences such as language, culture and art mediums. Thus I am writing to you in the kind of confidence in which an unknown person to you perceives himself as an old friend, one who feels kindred both in spirit and in art.

For about a month I have been working, in my house in Grizzana, on a series of landscapes in which I have been looking for new spatial and chromatic relationships between the elements of the composition.

In the article I found on the internet, the image below was included, plus a footnote (#3) which states: "Morandi is referring to a series of five paintings, executed in 1961, in which the motif of a house peeking out from behind trees is repeated. Specifically, the painting he speaks of in the letter is the landscape belonging to the Morandi Museum ("Landscape", oil on canvas, 50.5 x 30.5 cm, 1961), part of a group of forty landscapes, which were painted between 1959 to 1963 and according to some historians represent the pinnacle of the artist's pictorial expression."

Morandi, Landscape 1961

This morning, on the train that took me back to Bologna, I realized that I have never before formulated such a question in my mind because technique is always an occurrence of an inner vision or impulse, therefore there is no way of representing things seen--or heard--in only one way that could generate a feeling of universal value.

It is generally thought that following a meaningful experience of a thing or event that generated the impulse to make a painting or create some music, it is possible to obtain its form in a particular style--rather than another. But articulate expression is the result of an intuitive impulse, never a consciously created intention, since it is precisely the artistic discourse, the truest and most profound one, that belies the relationship between one's gaze and everyday reality; a discourse that transcends one's desire to create a "tailor-made" gesture each time.

On the edge of naked reality, beyond any objective evidence of a given thing, an artist's gaze can afford a certain degree of myopia, pushing his seeing into the space where the world we already know has a second life. So every work of art is nothing more than the possibility of having other eyes, of manifesting a reality that is no longer in front of us, but which is embedded deep within one's very being.

Your music, if you will allow me to say so, Mr. Monk, seems to me to be of that quality which is able to grasp the essence of a musical discourse . . . not so much in your ability to give dignity to the instrument you use [the piano] but rather in putting the instrument aside, leaving the sounds, alone, to create anew--in articulate alignment--the essential inner vision or feeling which sparked the impulse to create. In this regard your music, it seems to me, is similar in essence to the music of Bach or Mozart, whose art is of a perfection that transcends time, cultures, the limited histories of humanity; an art that belongs to the realm of being that gives the weight of deep meaning to the short life of a man.

With renewed esteem and gratitude,

Yours truly, Giorgio Morandi

Morandi's experience at Monk's concert--just three years before Morandi died--provided him with deeply personal revelations about his own creative process in painting, and more generally the power of art to communicate in ways that transcend differences of culture, race, language, medium, etc.

*

Monk's music, and the music of many other composers have been a powerful source of inspiration to my creative process in photographic picture making going back to the late 1960's when I was an undergraduate student. (click here to learn more about the music that has influenced my work). It remains a mystery to me how it works, though Carl Jung's theory of Synchronicity and Alfred Stieglitz's theory of Equivalence have provided me with some useful insights. (My 1972 MFA Written Thesis explores these two ideas which continue to be relevant to me today.)

When I hear Monk's music, especially his solo piano performances, I too am fascinated by his unique, unorthodox style, including the way he held his fingers stiff during performance which permitted him to play the piano with great percussive power. (See the video Straight No Chaser) And Monk's use of dissonant sounds, angular melodic changes, unusual uses of repeated phrases, and unpredictable spaces of silence, hesitations, odd lingering pauses . . . and the ever changing arsenal of techniques he used to transform those familiar, simple tunes with which he would begin his improvisations . . . all of it and more adds up to a mystery which nonetheless can have, for a visual artist such as myself, corresponding visual counterparts.

The grace which is at the True Heart of any intense, sincerely searching Creative Process is beyond the limited human mind's ability to understand; however I know from my own experience that Monk's music transforms me, refreshes me, energizes me when I listen to it closely, intently. His music has been a vital inspiration that has affected my vision photographically over and over again.

Critics have written that they can hear Monk "thinking" and "questioning" as he spontaneously improvised on his own and others' familiar melodies. I am not sure "thinking" is quite the right word here, but I believe I know what the writers are trying to get at. It is well known by jazz musicians close to Monk that he put endless hours of intense practice, truly great effort, into his music. That degree of discipline and self-effort can impact one's creative process in very liberating ways. The yogic saints tell us that self-effort and grace are the two wings of a great and beautiful bird. Monk soared like a bird when he performed his music.

(Listen to the album Thelonious Himself, on the Riverside Label, which contains two cuts devoted to Monk's composition "Round Midnight" one of which documents his extended process--over 21 minutes long--of searching for new ways of treating his own 1944 composition which had already become a jazz standard by the time he made the 1957 recording.)

*

Perhaps Morandi had recognized something of himself in Monk's wonderful, surprising, quirky, beautiful music. Those simple, charming melodies that Monk created in his own compositions, and the familiar melodies he chose to perform from popular tunes and traditional jazz standards--tunes he performed over and over again--served merely as points of departure for Monk's remarkable improvisations that unfolded through his spontaneous, inventive graceful use of all kinds of transforming techniques that he had developed throughout his life, beginning at a very early age. Each performance of the same familiar tunes reveals significant new insights and creative differences which the vast achieve of his recorded music makes very clear.

Similarly, Morandi painted--over and over again--the same Grizzana landscapes surrounding his beloved mountain village where he and his sisters would spend the summer months; and of course--over and over again--he created a seemingly endless number of arrangements of his famous collection of dust-covered old bottles, boxes, dried flowers and vases, and then would carefully, slowly contemplate what he was seeing before beginning to place paint onto canvas with his very delicate and spontaneous touches of the brush. Though he painted the same places and objects repeatedly throughout his life, the completed paintings represent an ever changing array of transformations which provide an infinite range of evocative feelings and intuitive visual insights. Belying most of his paintings I can feel a vibrant, creative, unifying force that expresses inexplicable things.

All this is to say that Monk's use of familiar melodies, and Morandi's recurring use of familiar subject matter was but a means by which they each could give created form to subtle manifestations of spiritual presence. I feel kindred in spirit to both of these great artists. Their works function for me as mirrors which continue to unveil layers of ever-changing meaning within me. I love hearing and seeing and contemplating their works over and over again. Monk's music and Morandi's paintings refresh me and inspire me to make creative worlds of my own.

*

Morandi died in 1964, less than three years after hearing Monk's music. He must have been suffering horribly in those last years from the lung cancer which had been bothering him for many years before. But Monk's music opened Morandi's heart one night and provided him with new ways of understanding his own creative process as a painter. His letter to Monk is a wonderful testament to Monk's creative stature, and it's a beautiful testament to Morandi's greatness as a person, one who was willing to be open and receptive to new and meaningful experiences and influences. The letter he wrote to Monk overflows with authentic enthusiasm, joy and gratitude--the kind of creative energy that was similar to that which Monk allowed to flow into and through his music.

That grace-filled moment in Milan, when Morandi crossed paths with Monk and experienced through Monk's music something deep within himself that he'd been searching for was, it seems to me, a meeting of two souls in which a discourse had occurred that transcended words in any language, or any other possible obstacles. It was an experience that changed Morandi's life, and Morandi, recognizing this, shared his experience and his feelings of gratitude with Monk with a heartfelt letter.

Monk's music and Morandi's painting have helped me to understand that we all are connected by a dynamic universal creative energy; that we are all connected in the same One infinite space of the Heart, a space that knows no boundaries. Monk's music, Morandi's paintings and Morandi's letter to Monk have inspired me to create this project as a tribute to the both of them. And it is with great gratitude that I welcome you to this project.

For a brief overview of Monk's life and career as a composer and pianist, check out these two links:

And, again, I invite you to see my two project links which are tributes to Morandi:

Regarding the Photographs in this project

All of the photographs presented below were made in the summer of 2021 while I was working on other projects, including my second hommage to Morandi, The Light of Memory. Some of the images were made after I had learned that Morandi had written a letter to Monk. This is an important detail, I think, because upon learning about the existence of the letter I began listening to Monk's recordings over and over again (mostly his solo piano recordings). I feel certain the music influenced some of the photographs I have made during the past four weeks, and perhaps my choice of images included in the project. It has seemed to me, over the forty years I've been listening to Monk's music, that its creative energy has had a liberating affect upon me; that it has given me permission to try new or more radical ways of seeing and making photographs, and choosing images for inclusion in projects which challenge some of the old habits I have fallen prey to.

For the past two years or so I have been listening almost exclusively to rather quiet, contemplative kinds of music, and I have continued to do that as well in regard to Monk's music. There are many wonderful solo recordings Monk has made in which he plays slow, moody, contemplative music. And, even in those recordings there can be surprisingly playful, humorous musical moments, and brief unpredictable flourishes in the midst of a quiet composition which contributes to the overall meaning and creative spirit of the work.

(Note: one album I highly recommend in this regard is The Art of the Ballad by Thelonious Monk which is an excellent compilation of slower, quieter Monk compositions and jazz standards, several of which include duos with John Coltrane and others.)

Though I cannot say that any of the photographs in this project were made with this project consciously in mind at the time I made the exposures in my camera, I know that Morandi's painting, and his letter--its content and its energy--has influenced my creative process in unconscious or intuitive ways, just as Monk's music has. The fact is, I have seldom succeeded in making meaningful images when I am trying to give visual form to a specific agenda or intent. In that respect I was very interested to discover, in Morandi's letter to Monk, that he too felt the same way:

It is generally thought that following a meaningful experience of a thing or event that generated the impulse to make a painting or create some music, it is possible to obtain its form in a particular style--rather than another. But articulate expression is the result of an intuitive impulse, never a consciously created intention, since it is precisely the artistic discourse, the truest and most profound one, that belies the relationship between one's gaze and everyday reality; a discourse that transcends one's desire to create a "tailor-made" gesture each time.

Actually, I have found it to be quite helpful to make a conscious effort to not think when I am photographing. Thinking can become an obstruction to my Creative Process. The great soprano sax performer and composer, Steve Lacy (who studied with Monk informally and performed Monk's compositions frequently in his concerts and recordings) often spoke of striving to "serve" The Music. This means to me that he wanted to get his ego "out of the way" so that the grace (the Creative Power of the Universe) could flow unobstructed through his Creative Process, giving full, pure voice to The Music.

As I was working on this project I looked back (several times) at my earlier Monk-inspired project Monk's Quirky Music. I like the Introduction to the project; it includes some important information and ideas that I feel are equally relevant to this project. If you haven't seen the project recently, I encourage you to do so.

After the presentation of the photographs, below, I invite you to check out the commentaries I have written on several of the images.

Note: if you have a viewing device that will allow you

to see the photographs in a black or darker toned

viewing space, I encourage you to do so.

(Try clicking once/twice on these photographs.)

The Photographs

_________________________________________________

Image #1 Monk's Red Brick

Image #2 Monk's Bird Ascending At Daybreak

Image #3 Monk's Light in Water

Image #4 Monk's Way of Saying Goodbye

Image #5 Monk's Dancing Shadow

Image #6 Monk's Reflection in Silver

Image #7 Monk's Cloths Lines in the Early Morning Light

Image #8 Monk's Letter from Morandi

Image #9 Monk's Cloths Rack

Image #10 Monk's Smiling Face

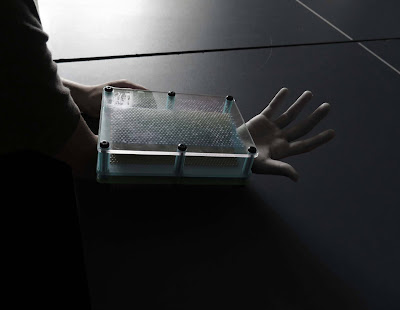

Image #11 Monk's Playful Drumstick Fingers

Image #12 Monk's Glove

Image #13 Monk's Lace Curtain

Image #14 Monk's Cloths Hangers

Image #15 Monk's Swatch of Light

Image #16 Monk's Musical Path of Light and Shadow

Image #18 Monk's Water Fountain

Image #19 Monk's Foggy Morning Bird and Puddle

* * *

Commentary

on selected photographs

_____________________________________

Click on the images to see them enlarged and possibly presented in black space

This image seemed the obvious choice for the project's title photograph. The letter (or mark) "X" is sometimes used to authenticate an important document in lieu of an individual's signature, and in that regard the X represents for me the letter Morandi wrote to Monk, for I feel as though I have not yet seen the actual letter because the English translation I have had access to so far has been difficult to understand. ~ I also associate the X with two intersecting brush stokes one might discover in a Morandi painting; and it could signify the meaningful coincidence of Morandi and Monk "crossing paths" with each other at a jazz concert in Milan. The unlikely, unintended meeting--in which no words were spoken between them and yet somehow Monk's music gracefully resolved for Morandi some pressing problems he was having with a series of landscape paintings at that time--is a perfect example of synchronicity, a theory C.G. Jung wrote about which has been of crucial importance to me in relation to my own creative process in photography. (Click here to learn more.)

I don't know how the X mark got imprinted on our picture window. It became visible to me one foggy morning when the moisture condensed on the outside surface of the glass. Maybe the man who cleaned the window weeks before left the mark with two strokes of his squeegee; or perhaps a bird had left the mark on the glass after it accidentally flew into the reflected image of a clear sky one early summer evening. (See these two related projects: Picture Window Photographs and Window Pictures)

___________________________________________________________________________________

I had placed my easel in the garden in front of the two trees

from which you can see a glimpse of the house in the back.

Morandi refers here to a series of five paintings executed

in 1961, the year he attended Monk's concert.

I was a bit startled when I realized how similar my image was to Morandi's 1961 landscape painting that accompanied the online link which contained the Italian text of Morandi's letter to Monk. I had decided on including this image because of the bird that seemed to be looking at or contemplating the puddle that had formed in our driveway. Truth be told, I was reluctant to use the image in this project because I have had an aversion to including the relatively new houses in our community's development within my landscape photographs.

But more recently, because of my renewed interest in Morandi's landscapes--most of which include at least a minimal reference to an architectural presence--I have been infrequently allowing houses to appear in my own landscape photographs. In this particular case the fog provided something like a ghostly architectural presence that formally echoed the relationship between the bird and the pond. Houses served Morandi's landscape paintings in a way similar to how he used his famous collection of small boxes (and other well known objects, such as bottles, vases, funnels, etc.) in his still life paintings.

*

I love the way fog transforms the world. (See my projects Creation-Dissolution of a World and Images of Eden.) There has been a lot of morning fog this summer, partially mixed at times with smoke that has drifted over to us from the wildfires in the Western States. There is a sense of timelessness in the way fog affects my perception of the world. When I see things, such as houses or trees or ponds on a foggy morning, they seem caught, stilled in the process of either emerging from or merging into the fog. In this regard, fog is an interesting metaphor for the Creative Process: for who can understand how the music Monk has made, the paintings Morandi has made . . . or the photographs I have made . . . come spontaneously into existence charged with a feeling of ineffable meaning? Isn't it the same mystery that lurks within the primordial story of Adam & Eve and the Garden of Eden?

There are two other "bird photographs" included in this project. This one was made on another foggy morning, just as the sun was beginning to rise above a sloping rooftop. The dark leaves on two tree limbs above the bird in the background share similar formal characteristics with the bird's form and its wings outstretched. These three dark forms constellate an image of roundness. It seems as if the forms are flying or dancing or chasing each other in a circular movement with excited enthusiasm, perhaps in celebration of the eternal re-emergence of light from the morning's rising sun.

Gaston Bachelard, in his wonderful book The Poetics of Space wrote at length about birds and their "roundness of being." I invite you to visit my project Looking At the Overlooked, which is the fourth chapter of my multi-chaptered project Still Life, my first project in hommage to Giorgio Morandi. In that chapter there is a section devoted to birds and Bachelard's poetic meditations on the "roundness" of bird nests, intimate space, centeredness and "the soul becoming form."

Bachelard wrote: "Because every universe is enclosed in curves, every universe is concentrated in a . . . dynamized center. And this center is powerful, because it is an imagined center." When he wrote about the intimacy of the round space of bird nests, he included a line that I truly love and have always remembered:

Every object invested with intimate space

becomes the center of all space.

As I was writing about the image of the bird, the puddle and the house in the foggy background, it occurred to me that I had concluded this project's collection of photographs with an unlikely image of Canandaigua Lake. I say "unlikely" because I have lived in Canandaigua, NY since 2008 and though I have often felt the impulse to photograph the lake, I have usually avoided making the pictures . . . probably for two reasons: 1) because of all the Lake Photographs I had made in 1981-82 of Lake Michigan from the shores of Milwaukee, Wisconsin: and 2) because I don't like seeing all the houses which are situated on private properties all around the Lake's edge.

Compared to Lake Michigan, Canandaigua Lake is like a puddle. But because of all the beautiful rolling hills that surround the Lake, the space over the water often has a beautiful, intimate round presence--like a bird's nest--filled with a subtle but palpable living luminessence.

I enjoy watching how changing weather and light conditions transform the space above and around the hills surrounding the Lake. And I especially like it when the fog dissolves the appearance of houses situated along the water's edge. Fog has the ability to transform Time as well as space. I remember an experience in which I became enveloped in fog as I was photographing, when space and time became undefinable, when I became aware of my own primordial presence which, in other moments, had seemed to pervade large bodies of water, large stretches of land, and the vastness of space above, below and all around . . .

This photograph was made just after the fog had lifted, and perhaps just after I took the photograph of the bird by the puddle. I enjoyed the sense of stillness, harmony and purity of everything before me; but then I began wondering abut the dark wooden pier that protrudes into the water from the picture's left edge. Should I remove the dark shape? Finally I decided it needed to stay . . . perhaps to add a formal balance to the image; perhaps because the pier reminded me of the bird by the puddle, which seemed to be contemplating the puddle. I imagined the dark shape as a living form of consciousness that was contemplating all the surrounding beauty, the stilled water, the silvery light, the self-luminous bank of clouds rolling over the hills' edge.

When I took this photograph I was deeply touched by the scene's harmonious stillness, the way all the forms were repeating and echoing each other in a symphonic-like sustained moment of silence.

Both of these photographs were made in our basement, and both involve the ping pong table and the idea of "play." Both also include, in different ways, the presence of my eight-year-old grand child, River. When he and his mom visited us this summer, River and I spent quite a lot of time playing ping pong with each other, and with Claire, his five-year-old cousin.

When I saw River put his hand through the insides of the plastic toy he was playing with, I asked him to "hold it!" (please) so I could get my camera and take a picture. I remember the thought "bionic arm" passed through my mind as I rushed upstairs to get my camera. However, the image now reminds me of Morandi's fascination with the way Monk held his fingers straight "like drumsticks" while playing the piano.

The other image--a symmetrical configuration of five ping pong balls lined up on the table in the space between the two halves of the table, with paddles on both ends, their handles pointed in opposite directions--looks and feels to me like a secret visual-coded message. I like to think of it that way, at least, because River created this constellation just before he and his mom left to go back home to Milwaukee. When I went downstairs the following day and saw what he had created and left behind, I interpreted what I saw as a good-bye "letter" which said something like: "Thanks, Grandpa, I had fun playing ping pong with you. Love, River."

The rubber rings in the foreground, which River and Claire and I had played with together, were placed on the table by me, as a kind of response to River's "letter." Of course now I also think of Morandi's letter to his new-found friend and kindred spirit, Thelonious Monk. I also think about how Morandi would contemplate the still life configurations he had constructed on the tops of tables near his bed in his Bologna studio, trying to find just the right relationships between things and spaces that would communicate some unknown, unsayable meaning that had emerged from within his meditative creative process.

Truly, there is no end to the creative, spontaneous, playful things you can do with some ping pong balls, paddles and colorful rubber rings. Playing with five and eight-year-old kids can be a lot of spontaneous, improvised fun. In that regard I also like to think of Monk and his piano playing--which so often is filled with child-like, fun-loving, spontaneous, improvised and often humorous creative energy.

Morandi was playful in his painting too, but in a much quieter, gentler, secretive way. Especially late in life his paintings would present various kinds of perceptual "games" in which the spaces between objects in his still life paintings became fascinatingly ambiguous and at times difficult to decipher. I like the way negative spaces become transformed into apparently solid objects in many of his still lifes, and I like the way various objects in his paintings would merge into each other so that you could not tell which object was in the foreground and which one was in the background . . . or . . . if one object was really there, or not. Sometimes objects in his paintings were just barely visible, as if a ghostly presence.

I must write about this image though I am uncertain about why I took it the way I did, what it means, or why I included it in my project. I often write comments to learn the answers to such questions though I also know that there are no definitive answers in many cases. ~ I made the image this summer while visiting the Sonnenberg Gardens (a NY State Historic Park) with River and his mom. (Note: images #1 and #16 were also made in Sonnenberg Gardens.)

This is what I would call a quirky image of a water fountain in Sonneberg's formal gardens; its oddness has mostly to do with the extreme point of view: looking down over the top of the head of a sculpted figure perhaps representing some water sprite or other mythic character. The view allows us to see two rings of light rippling over the water's surface, a shadow that looks something like a bird flying by, and several coins which are laying under the water on the fountain's concrete bottom. And next to the head there is a constellation of bubbles floating in the water over a dark space. The bubbles could be emblematic of the sculpture's thoughts or breathing, and the two rings of light create a form that suggests the number 8, or perhaps the symbol for infinity. But, for reasons unknown to me, it's the gesture of the figure's arm and hand--which seems to have reached out and then rested upon something like a pedestal--that draws most of my attention.

I associate the fountain picture's "quirkiness" with those miniature photographs I made throughout 1994-2000 for a project I entitled Studies I, some of which I selected and used in my hommage to Thelonious Monk in 2011, Monk's Quirky Music. My interest in the fountain figure's gesture seems to have invoked the memory of another image I had made for the Studies project (a man lifting his leg in the air as he's stepping over a low wooden barrier) which I have presented below.

The fountain image (which exists somewhere between color and black&white) and the Studies photograph (which is black&white) have also reminded me that I have not made many photographs of the human figure over the past several years. Many of the Studies photographs, including those I selected for my Monks Quirky Music project, contain the human figure . . . and I do mean really quirky images of the human figure, often involving ambiguous gestures. I have provided five additional photographs, below, from Monk's Quirky Music all of which share similar visual characteristics that relate to the fountain photograph's highly stylized figurative gesture.

All six of the images below have a certain kind of ambiguity of meaning, which it seems to me is based in the figure's gesture and the moment in which the gesture was photographically suspended in Time. The images do not reveal the intent of the gesture or its resolution. In other words, the meaning of the photograph remains essentially unknown, unresolved, and will remain a tension held within the image . . . forever.

We viewers and contemplators of such images do have, however, a few options. We can manufacture, or imagine a narrative that will generate some closure or resolution to how we could understand a meaning associated with the image. In this regard, the "Monk titles" I have given the photographs could provide you with a point of departure toward a resolution to the meaning of the image. But it must be understood, I cannot tell you or anyone else what an image means, even though I made the photograph. In fact, typically I do not think of my images in narrative terms. My "Monk titles" are a way of trying to join with Monk in the spirited way he uses of humor in his music. Therefore it is each viewers responsibility to find their own meanings from within their own selves.

There is another way of accessing that meanings. It is very different than making something up. I refer to this other way as Contemplation. It involves going inside the image and inside one's own Self (one's own Heart) and "listening" to that discourse in which no words are spoken. This process is about receiving rather than "manufacturing." Contemplation allows each viewer to take full responsibility for the meaning they receive from of any given image at a given moment in time, understanding that meaning is being determined not by self-will but rather by opening to one's own unique nature and ever changing capacities . . . as in, for example, the best examples of improvised jazz music. For, even if the same image is contemplated at different times, the outcome will potentially be different because the image will mirror or invoke certain aspects of one's Self which have emerged since the previous viewing.

Contemplation works best for me with images that are functioning for me as True, living symbols. The symbolic photograph is open-ended in meaning, and as such are in need of our prayers and Heartfelt empathy which can only be achieved through a silent Heart-to-Heart conversation.

___________________________________________

Monk's music and Morandi's paintings will live forever because their art functions at a deep level of True, open-ended symbolic meaning. Morandi recognized and acknowledged this quality in Monk's music when he concluded his letter of gratitude by writing . . .

. . . your music is of a perfection that transcends time, cultures, the limited

histories of humanity; an art that belongs to the realm of being that

gives the weight of deep meaning to the short life of a man.

from "Studies I, 1994-2000"

*

from "Monk's Quirky Music" Monk's son became a drummer

from "Monk's Quirky Music" Monk wrestling in the snow

from "Monk's Quirky Music" "We see" Monk

from "Monk's Quirky Music" Monk's race

from "Monk's Quirky Music" Monk playing on a ladder

This project was announced on my blog's

Welcome Page September 23, 2021

Related Project Links:

Still Life July 2013 - July 2014 A multi-chaptered project in Hommge to Giorigo Morandi

Welcome Page to The Departing Landscape blog, which includes the complete hyperlinked listing of my online photography projects dating from the most recent to those dating back to the 1960's. You will also find on the Welcome Page my resume, contact information . . . and much more.

.