Homage to Giacometti Part 3

Figures & Triadic Poems

Photographs Inspired by or Related to the Paintings,

Drawings & Sculptures of Alberto Giacometti

1. Introduction : "Portraits" Heads Faces

2. Line-Drawing Photograph Portraits

3. Figures & Triadic Visual Poems

4. Landscapes, Still Lifes, Place and Presence

5. Regarding Giacometti's Fear of Death

6. Vision, Re-vision and "Recurrence of Creation"

7. New Work, Commentaries, Epilogue

Introduction

A few years ago I received an email from a woman inquiring about one of my photographs she had seen exhibited in a Milwaukee gallery years ago. She often thought of the image and was hoping to get the photograph, if possible, for a visual shrine she had created for her son who, tragically, had died at a very early age. The picture reminded her of her son, and felt its inclusion in her collection of images on a wall in her home would perfectly complete her memorial. It was a miniature photograph, a silver gelatin print from the Studies project, only 3.5" square, of a young child walking, happily it seems, into a vast space of whiteness, or light.

1. Little Boy Waling Into the Light 3.5x3.5"

We had had a long discussion back and forth via email that went on for over a week. I was able to find a print and I sent it too her. Strangely, about a year later, I realized that I had accidentally deleted all of our emails to each other. The whole experience had simply disappeared.

I am mentioning this experience here because it relates to a particular period in Giacometti's work, during the war, when he lived away from Paris for over three years, in Geneva, where he spent his days making little figurines in plaster, some not over an inch or two high including the base. He would obsessively keep cutting away from the plaster form, and the figure would get smaller and smaller . . . until finally the figurine disintegrated in his hands . . .

The miniature Study photographs are very important to me. Their smallness (3.5"x3.5"), which is part of their charm, often remind me of the life-changing epiphany I experienced when I was ten years old. See my brief essay, "Epiphany of 1955" on the Welcome Page of my photography website.

There has been some fascinating things written about the small figurines that Giacometti created between 1940 and 1950. Below are some examples of his work from that period. The pieces in Fig. 2 were made around 1944-45, the tallest sculpture of the three is only 4 inches in hight. I have also included an image of Giacometti working on one of the small figurines in his small hotel room in Geneva in 1944, the year before he moved back to Paris where he experienced a life-transforming epiphany (see part one of the Giacometti project).

2. Giacometti, Plaster figurines on large bases 1944-45

(click on the images to enlarge)

3. Giacometti, working on a plaster figurine, Geneva, Hotel studio, 1944

James Lord wrote of the tiny figurines:

Sometimes the figure grew so minuscule that a last touch of the sculptor's knife would send it crumbling into dust. He was working at the limit of being and on the frontier of non-being, confronted with the sudden passing of existence into nonexistence, a transition which took place in his hands but over which he had no control. For twenty years he had been obsessed with life's frailty. Now, it presided over his work. In a very real sense, it became his work. . . . [Giacometti once said:] "And it is in their frailty that my sculptures are likenesses." It is very fitting that very few of those tiny figurines survived. Their impermanence was their importance. James Lord, Giacometti, A Biography pg. 178

Giacometti continued working on the small figures after he returned to Paris. He also created little sculptural compositions in which the varying heights of the figures and the space between them became as important as the figures themselves. He then began placing the compositions on large, tiered and sometimes very high bases to increase the sense of distance between the sculpted figures and the viewer.

4. Four figures on a bases 1950 6 feet high

5. Giacometti, Four women on a bases 1950

6. Giacometti, "City Square" 1948 9" high

7. Giacometti, "At the Sphinx" 1950 Ink and mixed media

There is a similar evolution of figurative presence in my own creative process. I photographed figures and small objects in my miniature Studies projects, and in 1998 I began making visual poems with three or four of the Studies images, placing the silver prints in horizontal constellations of three images, and vertical constellations of four images. When I began making digital prints, in 2003, I would digitize selected studies photographs and isolate and suspend the figures and objects in large black spaces. Then I made "visual poems" with those digital images surrounded by black space. I put three carefully selected images suspended in black space together in a long rectangle of black space. Though I am not aware of being influenced by Giacometti's compositional arrangements of the figurines, and similar images in drawings and paintings, there are obvious similarities between my "poems" and Giacometti's compositions.

There are two sets of Visual Poems, one for the Feldman inspired Homage project Triadic Memories, and the second set was for the Feldman inspired project The Departing Landscape. For a brief visual summary of this transition to the visual poems, scroll to the bottom of this blog page: Studies 1994-2000.

In the Poem immediately below, the tones of the small child image has been inversed; now the tiny figure is white in black space and it has been placed with two other figures, both negative images as well in black space. How the child relates to the other figures is uncertain. Perhaps the poem is an allegory about time, growing old, departing, dissolution or death.

I intentionally constructed the poems in such a way that the viewer would have to make their own decisions about how and what the images meant to them. Although clearly a narrative is implied, in my opinion the meanings invoked by the three images placed together are open-ended. A new visual unity, a poetic Imaginal reality is invoked in the viewer by the interaction he or she has with the set of relationships between the images. There is an ongoing silent dialogue between the images in any of the poems, and the viewer is invited to listen, and even participate in the "conversation" by imaginatively entering into the space between the images. In this "four way" conversation the meaning of each separate image is impacted by its relationship to the other two images and then the imaginative participation of the viewer.

8. Foster, Triadic Visual Poem 27x15"

9. Foster, Triadic Visual Poem 27x15"

10. Foster, Triadic Visual Poem 27x15"

11. Foster, 12x12 Triadic Visual Poem Negative/Positive 12x12"

I am not sure what is appropriate to say about the relationships I am suggesting exists here between my photographs and Giacometti's figurative sculptures, drawings and paintings. As far as I know my images came out of a genuine need within my own creative process to satisfy particular problems at the time I made them. They were not, as far as I know, intended to refer in any way to Giacometti's work. But I see and feel that there is a relationship.

I should reassert, here, what I wrote in my introduction to the Homage to Giacometti project. I recognize that there are certain visual and conceptual relationships in my work to his; perhaps some of my work was inspired by his work, but perhaps my works are only related to his in the most obvious and yet unintended ways. What is most important to me, and true, is that I feel kindred in spirit to Giacometti and his work. I have learned from from studying his work and his life, and I've been inspired as well.

I believe that whatever it is I find meaningful in his work, it's because I carried that meaning within me, within my psyche, my heart, my creative process, from the very beginning of being. That is to say, it was already inside of me waiting for the right time and the right way to be manifested into external, photographic visual form. When I see relationships between my work and Giacometti's, I understand that I am simply recognizing some aspect of myself, my vision, my beliefs, something essential within me and my creative process.

Shrinking Man

Giacometti's tiny figures set atop a large base creates a tremendous sense of space, a distance similar to how we see figures far away from us. Such small figures appear to us primarily as a presence; there are no details in the figures we are seeing, unless we project the detail imaginatively from memory into the perception in that moment. Presence is enough; details can distract from something more essential. The recognition we experience in the tiny figures is internal, perhaps some essential aspect of our own Soul or Self.

Giacometti wrote and spoke often about his experience of seeing figures at a far off distance, in the immensity of space. For example:

I had an English girl-friend. And the sculpture I wanted to make of this woman was exactly the vision I had had of her when I saw her in the street, some way off. So I tended to make her the size that she seemed at this distance. It was on the boulevard Saint-Michel at midnight. I saw the immense blackness of the houses above her, so to convey my impression I should have made a painting and not a sculpture. Or else I should have made a vast base so that the whole thing should correspond to my vision. Giacometti speaking to Pierre Dumayet as quoted in Yeves Bonnefoy's Giacometti.

One of the earliest perceptual experiences of this kind occurred for Giacometti in 1937 when he painted Apple on the Sideboard. Yves Bonnefoy writes in his excellent book Giacometti that the painting (below) shows us "the ontological value of setting an object as far as possible from the observer. To look at something from a distance so that its oneness may be more apparent, and thus more significant of the act of being which underlies all that exists."

12. Giacometti, Apple on the Sideboard 1937 oil

However, there is also something profoundly intimate about looking closely, carefully, at small objects, objects at a distance, or objects depicted in small scale artifacts. Their minuteness and remoteness draws us closer and closer not only to the object but to the interior parts of our very own Self. Indeed, Giacometti's work is always about the inner world, and his small figurines make us go inside, through our vision and empathy, to the heart of what is truly real within ourselves and in those things we are seeing.

We enter a mode of being, an Imaginal world, a "place" between the image that appears to be outside of us, and the interior world of images within our own being. This world-between is a "transcendental world," writes Bonnefoy, "where we give shape to space," and "suddenly [the tiny objects or figures] can grow huge as the Milky Way . . ."

Similarly, James Lord writes in his biography of Giacometti:

Giacometti had wanted to renew his vision, to see with original freshness of what stood before him. He had not foreseen that the creations which embodied his vision would be symbols of regeneration. The sculptor's problem had become anthropological. Having determined to make a new beginning in his art by trying to work as though art had never existed, he made works which evoke the origins of creativity, its mysteries and rites. The tiny sculptures have something of the talisman, charged with anthropomorphic vitality and magical feeling. So they ask to be seen as inhabitants both of actual space, the space of the knowable and the living, and of metaphysical space, the space of the unknowable and the dead. James Lord, Giacometti, A Biography pg. 178

13. Foster, detail from a Triadic Visual Poem, "Man in Hat sitting in a Starry Night Sky" 27x15" (click on the image to enlarge)

One of the most memorable movies I saw as a child in the 1950's was The Incredible Shrinking Man. The ending of the movie still haunts me as I remember it. A man is shrinking, getting smaller and smaller, becoming nothing as he looks up into the night sky and contemplates the vastness of the universe, the stars suspended in darkness, the infinite growing closer and closer, larger and larger . . . Click here to see the finale of the movie.

*

Cecilia Brashi wrote an interesting essay entitled "The Sculpture was diminishing" for the two-volume publication Alberto Giacometti - Yves Klein (2017) by the Gagosian Gallery, London. She explores the idea of purification in relation to the tiny sculptures Giacometti made in Geneva during the war. She suggests that the reduction of detail which comes with the reduction in size of the figurines brings the artist closer to the "truest" representation of reality, regardless of the medium: sculpture, painting or drawing. And in so doing, a tense relationship is established between "interior and exterior forces" (quoting Sartre), that is to say, figure and ground, the visible and the invisible, the object and the void surrounding it. She concludes her essay:

In the end, the monumental power of all of Giacometti's figures, independent of their size, is linked to their capacity to resist these "forces," and even appropriated them with their own "internal power of affirmation" . . .

She then invokes the practice of the Amazonian Indians known as Jivaros who shrunk the skulls of their enemies. She writes: In shrinking the skulls . . . these indigenous peoples . . . hoped to repress their opponents' spirits . . . Reducing the skull was therefore the means of forever concentrating the spirit. Although through an entirely different approach, Giacometti was able, through reduction, to eternalize his model--in other words, to make visible, through an extreme and implacable exercise of diminution, that which resists the variables of time and space, the hazards of contingencies and transient appearances, and the infinite points of view that can be brought to a single subject.

Absolute Reality

Giacometti himself felt that the small figures were more real than most of his other efforts at getting at the truth of reality, the truth of what he saw and felt. But who would possibly take those tiny figurines seriously? Bonnefoy suggested that as we are plunged as deeply as possible into the abyss of the continually shrinking figures that Giacometti sculpted to the point of disappearance, to the point of nothing but dust in the hand, one can imaginatively enter into the ineffable interior world of being--that invisible point from which all that exists originates. He writes: "And perhaps if [a figurine] were reduced even further, it would attain absolute reality." (see my project The Blue Pearl.)

The Garage Series

Part of my collection of Studies projects includes a series of 3.5" square silver print Garage photographs. Many of the silver prints included black space above or around the garage forms. Then later, I tried suspending the garage forms in a 10x10" (silver print) black space. A third incarnation of the series finally evolved when I created the online digital version of the garage images. This time I suspended little garage forms in an even vaster (18x18") black space. Visit the digital Garage Series.

I thought of the garages as self-luminous jewels, or stars suspended in the vast unknown space of the universe. The images were also a metaphor for the sounds of a remarkable music composed by American composer Morton Feldman. He suspended beautiful piano sounds, and sequences of sounds, in what he termed a Chromatic Field, a merging of all the sounds played as they gently emerged from the Field, became suspended for a time (though the use of the sustaining pedal on the piano) in the Field, and then were allowed to naturally dissolve, decay back into silence. In my garage photographs, I thought of the black space as silence.

14. Foster, the Garage Series 1999-2001 (digitally printed 2006) 18x18"

15. Foster, the Garage Series 1999-2001 (digitally printed 2006) 18x18"

16. Foster, the Garage Series 1999-2001 (digitally printed 2006) 18x18"

17. Foster, Figure by Tree, 18x18"

18. Foster, Shadow Figure and crossed lines 18x18"

19. Foster, Figure sitting on plank, and leaves 18x18"

20. Foster, Boy with Bat and Ball 18x18"

Divine Figures

Giacometti was conscious of an aura, or halo around the people when he looked at them with intensity. You see this aura in his paintings. He once was quoted as saying: I have often felt, in front of living beings . . . the sense of a space-atmosphere which immediately surrounds these beings, penetrates them, is already the being itself . . . Quoted in David Sylvester 'The Residue of a vision' Alberto Giacometti : Sculpture, Paintings, Drawings 1913-1965 catalogue cited in Paul Moorhouse, Giacometti : Pure Presence 2015.

21. Giacometti, "Man in the Street: 1957 Oil

22. Giacometti, "Figures in the Street: 1950

Yves Bonnefoy writes about the aspect of Oneness in Giacometti's tiny, distant figures. In their smallness they manifest an aura, an energy, something like silence, the ineffable, the divine:

At various periods in religious tradition, there have been negative theologies, that is to say, theologies concerned with eliminating everything God is not, and this when looking ever more inwardly into what God's essence might have been thought to be: so that when all these blocks of knowledge are cleared away the invisible spring might gush forth. Any form of mediation, whatever can be put into words, is set aside so that the immediate, which is ineffable, may be made manifest. Now nothing is closer to this mystical process than Giacometti's way of working with his little figures, which he increasingly seeks to strip of all those signs by which mimesis denies itself the experience of Oneness.

These distant figures, suggestive of unity, are in fact divine figures such as are found in traditional cultures, whose sculptors had by force of what Alberto called 'style' transcended the disintegrating power of literal representation . . .

Giacometti's nephew, Silvio Berthoud, has stated that, during the war years, his uncle liked to tell him about Akhnaton, the great pharaoh who was concerned only with the unity underlying the multiple images of the gods, and to attain this had defied his priests and had conceived of a revolutionary and apparently extravagant art, which has a certain profound resemblance to the future art of Giacometti.

And Giacometti told Nesto Jacometti, who visited him in Geneva, that if he succeeded in reducing his figure to the size of a matchstick, so that one's gaze would no longer wander from one detail to another, the 'little fellow' suddenly would assume a 'godlike bearing.' Yves Bonnefoy, from his book Giacometti

23. Figure reflected in window Studies project, digital 10x10"

24. Walking Man by bus at night Studies project B&W digital 10x10"

25. Figures Walking in Death Valley, Studies project, digital 10x10"

26. Giacometti, Walking Man 1950 oil on paper

When Giacometti made his tiny figures during the war he transcended the detailed aspect of the human body by looking at his subject from such a far off distance that he could 'see' only presence. He could see only presence when those tiny figures became detail-less and thus like divine goddesses. After the war, however, and after his epiphany of 1945, his vision shifted and he strived to convey through his work the present moment, and the element of "wonder" in "life itself." He began to make images of man moving through space in time, and he represented the walking figure with the harshness of materiality itself. The course textures created my his obsessive, intimate, caressing and pinching of the plaster and clay became part of the experience of "life itself."

Yves Bonnefoy writes that in the work of the late 40's and thereafter Giacometti engages "the depths of the earth--hence the huge feet of his figures, rooting them lower than mind can reach. . . Giacometti simply experiences anew the act by which every living being rejects annihilation, while meeting himself with a comparable resistance--that of plaster or clay . . . Giacometti stands matter upright, making one think of those gods who created the human species by compressing around a spark of being the formless clay of primal days." Bonnefoy, Giacometti

27. Giacometti, Man Walking, 1960 Bronze 6 feet high

Walking and Standing Figures

In the elongated sculptures of walking men Giacometti is not addressing a particular person. It is the Everyman. The man is walking, moving forward, charging ahead into life; women however, are goddesses, eternal beings, larger than life, essentially a presence suspended in its timelessness, her arms and hands (usually) held tight against her body, as in ancient Greek sculpture which Giacometti loved and studied with great care and interest.

Giacometti once expressed his fascination with the very act of walking itself, the balance that it required, even the verticality of it which his sculptures emphasize; he once exclaimed: "walking is wonderful, simply wonderful." Though we usually take walking for granted, as we perform the act gracefully, if unconsciously, for Giacometti the act of making a sculpture or the drawing or painting of a man walking, or a woman standing, still, seems to have become for him a way of identifying with the "wonder" of life, existence and being in time and space.

And of course Bonnefoy waxes philosophical about all this, as he too embodies in his writing what Giacometti was thinking and feeling about the magical-creative nature of the phenomenon of walking:

But the forward movement of the leg is more than just a piece of external reality, since . . . it can and must be seen as a gesture immediately compensated by another gesture and resulting in the balance, 'from one foot to the other' which brings the observer to the plane of the essential reality, namely, the will to be, the fact of walking, the fact that one is. Bonnefoy, Giacometti

And Bonnefoy takes his reading of the act of walking to the very beginning of human life, when walking (and standing), and its relationship to the idea of balance, become emblematic of that archetypal moment "in which matter becomes life and human life attains self-awareness."

28. Foster, "Figure with head bowed, arms hanging down" Faint photograph 18x18"

29. Foster, "Figure standing behind lines" 21x21"

30. Giacometti, Staggering Man, Bronze 1950 23" high

31. Foster, Man Falling off ladder 18x18"

32. Foster, Man Climbing or Descending a ladder 18x18"

In the figurative work of the late 1940's and 50's Giacometti invents a new kind of representation of the Real, one that no longer seeks to create a lifelike figure but, writes Bonnefoy:

. . . indicates directly what must constantly assert itself inwardly in the model in order to continue existing on a non-visible, metaphysical plane. This single-mindedness of the artist disregards whatever does not have to struggle to exist; it is concerned only with that mystery. And the elongation of the figures, the way they seem to bear aloft their heads . . . which are now reduced to sheer vital energy . . . is simply and entirely the visible sign of this mystery . . .

33. Giacometti, Man and Sun 1960's Lithograph 12x17"

34. Dark figures under a bright cloud or perhaps the sun Studies digital 10x10"

35. Man Walking Away, Faint Photograph Studies, digital 18x18"

Studies a brief summary

The word I used to identify the little silver gelatin prints I made between 1994-2000 came from my love of brief little musical compositions, Etudes, which tend to be direct and to-the-point pithy musical epiphanies. I wanted my Studies photographs to have the same directness, the same reduced-to-the-essence seeing experience that I was having while listening to those piano pieces which somehow, in their listening, contained "internal images" I felt compelled to find visual equivalences for.

I quickly learned that the smallness of the image size demanded a new way of seeing and compositional structuring. Large forms and simple relationships needed to come together in just the right way within the square format, a way that looked and felt right when seen from a distance . . . at a glance.

In 1999, I discovered at the same time both the Milwaukee garages and the music of the contemporary American composer Morton Feldman.

So many things crystalized in my creative process around the year 2000, with my interest in Feldman's music and the use of black space, the visual poems and more. In 2003 I began translating the Studies photographs into digital images, isolating and suspending their forms in black space. Then came the digital visual poems.

Over the past ten years (2007-17) several new digital Studies projects emerged. Some were given conceptual titles even though I knew in my heart they were Studies projects.

To see a complete listing of online Studies projects click here.

There is for me an intense feeling of nostalgia when I remember that long, fascinating period of working with the miniature silver print Studies photographs 1994-2000. I felt so free then, so unencumbered conceptually. The work allowed me to intensify my seeing photographically while at the same time working in a relaxed, open-hearted open-minded state of inner stillness, peace, silence. I enjoyed looking closely at little things, and making little photographs of those little things. See, for example, the two images below, Fly and the Sliding Stone. They represent--for me--intimate, poetic moments of intense seeing, an affirmation, a respect, a love of nearly invisible things. And after all this, still the images are not without a touch of humor.

36. Foster, Fly Studies project 3.5x3.5 Silver Gelatin print

37. Foster, Sliding Stone Studies project 3.5x3.5 Silver Gelatin print

_____________________________

________________ * ________________

Paris Without End

'Oh! this desire to make pictures of Paris

here and there wherever life would take me.'

Giacometti, from the opening pages of his book

of lithographs: Paris Without End

published 1969

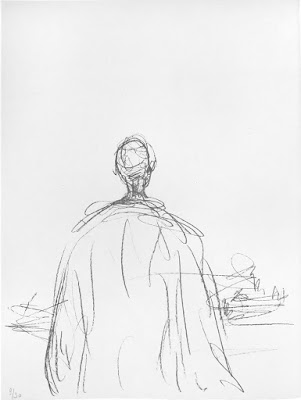

38. Giacometti, Lithograph 16x12, Paris Without End 1969

"Person from behind, and Paris in the distance"

Last Image, plate # 149 (before 1961)

39. Giacometti, Lithograph 16x12, Paris Without End 1969

"Crowd at an intersection"

Plate # 16 (before 1965)

40. Giacometti, Lithograph 16x12, Paris Without End 1969

"The Street, IV"

Next to Last Image, plate # 148 (before 1961)

In 1957 a book of lithographic drawings was planned between Giacometti and his old friend Teridade, a printer and publisher (Teridade founded for instance the famous surrealist magazine, Minotaure--with Skira--from 1933 to 1939). Giacometti agreed to the idea of the book if he could choose what it would be about and what images would be included. Giacometti worked on the lithographic drawings mostly between 1960 and 1962. However his carefully edited and sequenced collection of 150 lithographs, entitled Paris Without End, would not be published until 1969, three years after Giacometti's death.

The book is about Paris and Every man, Every woman. It is about Giacometti's Paris, how he experienced the great City day-in, day-out, in his studio, out on the streets, and in the cafe's and brothels he frequented at night. It was about the street life of Paris, and the printing shop where his book was being worked upon. He even included drawings of the printing machines. The book included street scenes, portraits, nudes and prostitutes--who for Giacometti were not mere women but "Goddesses."

Place was an important part of the book, but usually the human presence was to be found in most of the drawings, sometimes represented by nothing more than a simple squiggle of a line (see above Image #40). Many of the humans figures were universalized. That is to say, they were often represented with their back to the viewer. (Image #58).

Giacometti celebrated the spontaneous movements of people and automobiles in space. He drew from life as it unfolded before him with his lithographic crayons on sheets of lithographic paper. Many images are in the style of the "decisive moment" photographs his friend Henri Cartier-Bresson made. Giacometti even included in the book drawings of people dancing.

I am particularly interested in the drawing (Image #39) "Crowd at an intersection." It shows a complexity of simultaneous time-space events, of people crossing streets and cars buzzing by . . . images very similar to the photographs I had made in Atlanta, in 1975. (I have included two of the Atlanta photographs, below).

Yves Bonnefoy points out that there is a lightness to the drawings; a space through which light was allowed to illuminate the movement of life through the movement of lines. Even the blank pages, he suggests, which Giacometti used to help pace the sequence of images in the book, seems radiant with a light that projects out and into the images surrounding it.

Giacometti enjoyed getting out of the studio and becoming an active participant in the life of his beloved City. The act of drawing for the book, in the City, seemed to refresh and revitalize him. The work liberated him in a certain way, if only temporarily, from the exhausting, obsessive, and usually frustratingly disappointing work he continued at the same time in his dusty little studio, trying to paint portraits of his friends, and always feeling that he failed at capturing what he saw. Giacometti said:

Art interests me very much, but truth interests me infinitely more. The more I work, the more I see things differently, that is, everything gains in grandeur every day, becomes more and more unknown, more and more beautiful. The closer I come, the grander it is, the more remote it is. . . . but to succeed in portraying [my vision of the external world] it is almost impossible . . . Sometimes I think I can catch an appearance, then I lose it and so I have to start all over again. That's what makes me hurry onward.

Paris Without End permitted Giacometti to respond to life without limits, "without end." Anything could be subject matter. The book was his celebration not only of being in the world, but more precisely, being aware of life as he was living it in Paris, the place he loved. I can't help but identify with the importance of that project to Giacometti. As I've been writing about Paris Without End, I also been thinking about my experiences woking on the miniature Studies photographs I made in Milwaukee between 1994-2000.

*

There are many photography projects that prepared me for the Studies work, and there were many projects that were inspired, later, by the Studies project, such as The Dream Portraits, Family Life, The Walkabout Series (parts I, II, III, which were strange additions at the end of the Morandi Still Life project), and the recent The Zoo project.

And as I was writing about Paris Without End I was reminded of images I made for a 1975 project in Atlanta. Interestingly, when I searched for the Atlanta project, I discovered that I had for some unknown reason neglected to include the project in my blog's "Complete Collection of Online Projects." So I actually created the digital version of The Atlanta City Series project especially so I could reference it in this third part of the Homage to Giacometti project. I encourage you to visit the Atlanta City Series, 1975.

*

Below you will find a selection of images from the projects mentioned above. It will be obvious why I chose the images, how they relate to Giacometti's drawings for Paris Without End. For example: the use of the back of the figure (Every Man) looking out at the city; the presence of little human figures in the far background of images; figures walking, moving quickly though city space; figures interacting with automobiles at street intersections; images of family and friends . . .

In Giacometti's interior life, there was also the ever present presence of death, and the fear of death. I intend to devote an entire forthcoming chapter to this topic; and I have concluded this project with a visual Ode to the remembrance of death, an inexplicable but essential part of life.

In 1962, while still working on drawings for Paris Without End Giacometti became extraordinarily ill with stomach pain. X-rays revealed a cancerous growth. Four-fifths of his stomach had to be removed. Giacometti refused to change his unhealthy life style (constant smoking, working late into the night, eating cheap cafe food, not getting enough sleep), and he continued making art in his beloved Paris until the end. Giacometti died in 1966, at the age of sixty-six.

41. from the "Dream Portrait" project

42. from the "Dream Portrait" project

43. from the "Studies" project

44. from the "Studies" project

45. from the "Studies" project

46. from the "Atlanta City Series" project

"Woman Walking through downtown Atlanta in a black evening gown"

Giacometti, Lithograph from "Paris Without End"

"Crowd at an intersection"

(repeated for the sake of compare to the images above and below)

47. from the "Atlanta City Series" project

"Old woman and automobiles at an intersection"

48. from the "Walk About" project

"Two Men coming up airport escalators, Memphis"

49. from the "Zoo" project

50. from the "Family Life" project

51. from the "Family Life" project

_____________________________

________________ * ________________

Postlude

51. "Waving Goodbye" Triadic Poem for the Departing Landscape 27x15"

This project was posted on my Welcome Page

August 16, 2017

Homage to Giacometti, Projects List

2. Line-Drawing Photograph Portraits

3. Figures & Triadic Visual Poems

4. Landscapes, Still Lifes, Place and Presence

5. Regarding Giacometti's Fear of Death

6. Vision, Re-vision and "Recurrence of Creation"

7. New Work, Commentaries, Epilogue

Related online projects

Welcome Page for this website TheDepartingLandscape.blogspot.com which includes the complete listing of my online photography projects, my resume, contact information, and much more.