Photography and Yoga ~ Part 2 ~

The Ritual of Visualizing Sacred Worlds

Introduction Ritual of Visualizing Sacred Worlds

In the September 1998 issue of Darshan magazine, issue #138, there is an article by Dr. William Mahony entitled "The Artist As Yogi, the Yogi as Artist." He begins the article by raising questions about the yogic practice of contemplation and its relationship to the idea of "seeing reality" and the artist's cultivation of "insight." Back in the early 1970's when I was writing my MFA thesis, I considered contemplation the essential second part of the photographic creative process. That is to say, once the symbolic photograph was created through intuitive processes of perception (or "insight" by which there occurred a joining together of internal and external corresponding archetypal images--whose origin was the Self), it was through contemplation that the unconscious projected contents that went into the symbolic image could then be withdrawn from the image into a more consciously realized form of Self-knowledge.

Dr. Mahony's article sheds some light for me on the symmetrical photographs I have been making over the last few years. I will discuss this in some detail after I have presented the issues in Dr. Mahony's article which are relevant to my creative process. I should mention here, before getting started, that I am particularly fascinated by Dr. Mahony's exploration of imagination in the Vedic traditions since for the past several years I have been studying Henry Corbin's writings (including Tom Cheetham's contemplations on Corbin) about the role of Creative Imagination in the the Sufism of Ibn 'Arabi. (See these Corbin inspired related projects "An Imaginary Book" ~ The Photograph as Icon ~ The Angels)

*

dhi, rita, art & artist

Dr. Mahony states that for philosophers in ancient Vedic India it was the imagination that created reality, that is to say, the true, sacred universe. Vedic visionary poets knew that divine truths--as opposed to maya--were knowable only through the making of images that came through an internal process of inspiration. The Vedic word for the intuitive flash of the imagination was dhi.

The creative transformative power dhi, brought into reality "sacred knowledge" that allowed visionary poets to "see things as they really are" . . . to see "that the divine, the human, and the natural world fit together perfectly in an eternal and smoothly flowing symbiosis known as rta [universal harmony]" . . . and that "a poet who, through the intuitive genius of dhi properly put verses together, embodied the same creative power as the deities who through their maya created the world."

Dr. Mahony continues: "It is not insignificant that the Sanskrit world rita is derived from the Indo-European verbal root ar, meaning 'fit together,' and that the term rita itself suggests a rhythmic or smoothly turning wheel of being; for it is thereby related to . . . the Latin ars, which is the root of the English word art and artist."

"The Vedic sages who saw rita within and behind all forms of being saw the art of existence itself and--like the deities to whom they sang their praises--were themselves universal artists. They put things together correctly."

Ritual

Vedic priests, like the poets, could also create worlds--through the power of their ritual performances. The building up of sacred fires [yajna]was one of the most important Vedic rituals. Dr. Mahony explains: "The priests constructed an altar located at the 'head' of the sacred space; this altar was formed in the shape of a bird which was understood to carry the ritual oblations heavenward if the priests correctly performed the rite. In other words, having gained its power from the creative and purifying fires within the ritual 'body,' the bird flew out of the ritual's 'head' and into the heavens, carrying with it the transformative power to establish a new world. The ritual was, itself, a dramatic embodiment of creative artistry."

"Even those new worlds . . . were sometimes said to exist either someplace else, usually in the heavens, or at some other time, namely the future. The artistry that gave rise to them came to a large extent from the priests' powers of insight . . . Vedic ritual tradition taught the architects to think inwardly or to 'meditate' on the structure of the altar. In fact, the altars were known as 'structures' precisely because their builders had 'seen them intuitively.' According to this view, then, the sacred drama, like sacred poetry, rose out of the creative imagination."

The term dhi is related to the world dhyana which can be translated as "meditation" or "contemplation." Dr. Mahony explains that the term comes from the Latin con-templum, a two or three dimensional "space in which one is able to see sacred realities." He also points out that the English word temple comes from contemplari a word that means "to see things as they really are." Philosophers who composed the major Upanishads cultivated transformative insight through the act of contemplation.

Dr. Mahony writes: "Upanishadic teachings revolve around the central notion that the gods of whom the visionary poets had sung were in actuality reflections or embodiments of subjective processes within one's own being . . . 'All the gods are within me.' . . . Behind the spatial swirl and temporal flux of the external world as it was known by the senss lay a suble and pervasive reality the sages called . . . atman . . . the microcosmic innermost Self, which lies within and is identical with that ultimate reality."

Yoga

The word yoga technically means "harnessing" or "putting together." But Dr. Mahony adds: [the word yoga] "carries the sense of "procedure" and especially connotes the practice of joining the finite with the infinite." The various techniques of yoga are intended to connect or link different states of being. The yogi turns "towards the original source and ultimate end of everything." This is, says Dr. Mahony "a return inwards to the creative power of being itself."

"The Yogic practice of contemplation was said to lead the meditative sage to a state of samadhi, meaning, literally, 'put completely together.' . . . Samadhi has been said to be the highest achievement, the goal and purpose of all religious practice in the tradition of Yoga."

Visualizing Interior Divine States

Dr. Mahony goes on to discuss how adepts in the Yogic contemplative traditions visualized new modes of being by first imagining them and then externalizing these inner divine states and sacred universes as images in geometric shapes--often in association with specific images from the natural world.

Dr. Mahony writes: "Yogic meditators frequently imagined the sacred universe in the form of a circle surrounded by the leaves of the cosmic lotus, a flower that in India since time immemorial has evoked images of purity, enlightenment, and creativity. . . . The masculine creative power was often known as the god Shiva, while the feminine was frequently known as Shakti. The eternally creative combination of Shiva and Shakti within the harmonic unity of the sacred cosmos as a whole finds expression in a mystic diagram [yantra]. . . one of India's most sacred of artistic forms. It is said to bring benevolence and prosperity to all who look upon it."

Yantra

Meditators are often taught to visualize yantras within their beings, for example, within one's heart. These images of unitary reality then would lead to an experience of joining with the creative powers deep within oneself. When spontaneous images would arise, the contemplative was encouraged to give external visual form to those images. Because the images were sacred manifestations of unifying consciousness, they could then be used by others to aid in their meditative practices.

The contemplative practice of concentrating ones mind on a single external object or image enables the yogi to identify his deepest being with the image to such a degree that the dichotomy of subject and object dissolves. When this happens everything "fits together" and one experience the unity of the sacred universe, the divine Self.

Dr. Mahony writes: "The yogi who had cultivated this power of insight and thus had known the identity of subject and object could transform the objective world by changing the inner subject. Reality as yogis knew it was an artifact of their own inner vision, and they could change their world through the power of their imagination, and it was the practice of contemplation which made it possible for them to reach a certain kind of realization--in the sense of the making real (bhavana) of the inner presence of Divinity through the formative power of the imagination." All quotations are from the article The Artist As Yogi, the Yogi As Artist by William Mahony, published in Darshan #138, September, 1998

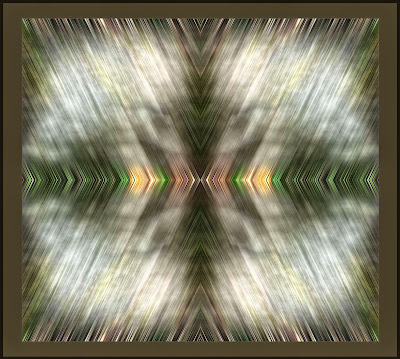

Photography and Yoga Image #3 "The Ritual of Visualizing Sacred Art" ~ Symmetrical Photograph - Imploding Cloud

Commentary on this photograph

The four-fold symmetrical photograph above was constructed from a photograph I took of a cloud that was floating in the sky over Gettysburg, Pa. while I was visiting the Military Park there. The image seems to me to be imploding, that is to say, all the lines of energy seem to be moving rapidly--as if in a flashing-forth--toward the center point or still point of the image.

Seen in the context of Dr. Mahony's article above, the image has for me some visual-formal resemblances to the Yantra he wrote about. As I contemplate the image I am taken imaginatively inside myself by the inward-moving energy of image.

This symmetrical image is a radical transformation of its source image. If I allow myself to contemplate the image as it is in itself--rather than think about the place where I took the image, and its history--the inward thrusting visual energy of the image takes me beyond God's play, God's maya, or lila, to the Self within. It serves as a creative, "heavenly" counterpart to its destructive earthly sight of horrific Civil War killings and mutilations, including exploding cannons, firearms and stabbings. The image turns my gaze within; it quiets my mind; it stills my entire being.

The image is an imaginative world that co-exisits simultaneously with an infinite number of other such worlds. Indeed, if you read the Vedic literature, this was true for the visionary poets. The following excerpt is from the Siva Samhita, an important ancient yogic text that was cited in Dr. Mahony's article:

In your body . . .

are two cosmic forces:

that which destroys, and that which creates. . . .

Yes, in your body are all things

that exist in the three worlds

[of earth, sky and heaven],

all performing their prescribed

functions. . . .

He alone who knows this

is held to be a true yogi.

I like to think of each of my symbolic photographs as a Loka, a transcendent world, a "temple" invoked from within by an imaginative state of being. As such the image has the potential of offering up to me as its contemplator--and for any other viewer--what the Yogic literature terms revealed, sacred knowledge, or Self-knowledge.

My symmetrical photographs are visual con-structions, not unlike the "alters" and ritual "worlds" created by Vedic priests and their intuitive, meditating architects. Indeed my process of making the symmetrical photographs is a highly intuitive, ritual-like process in which I "join together"or "unite" (yoga) four identical images in a burst of creative enthusiasm. Each symmetrical image has a center point which in itself is a metaphor for the source of all creation: the Supreme Self, or the Great Void: Mahasunya.

"Even those new worlds (writes Dr. Mahony) . . . were sometimes said to exist either someplace else, usually in the heavens, or at some other time, namely the future. . . . the altars were known as 'structures' precisely because their builders had 'seen them intuitively.' According to this view, then, the sacred drama, like sacred poetry, rose out of the creative imagination."

Dr. Mahony also writes about how adepts in the Yogic contemplative traditions imagined new modes of being and then externalized these inner divine states and sacred universes as visual images: "Reality as yogis knew it was an artifact of their own inner vision, and they could change their world through the power of their imagination, and it was the practice of contemplation which made it possible for them to reach a certain kind of realization . . ."

It is in this regard, then, that I consider my creative process in photography--and select images manifested through the process--associated with the sacred, the art of ritual, the yogic practices of meditation and contemplation . . . and the inspiration and grace of a powerful lineage of true Siddha Gurus.

*

Postlude

Two TeachingsPostlude

Baba Muktananda

and

Gurumayi Chivilasanada

Wherever You Look, See the Spirit That Animates Things

To look at the world with understanding in your eyes is an excellent form of meditation, for the Self pervades everything. Kabir speaks of "seeing in meditation." In fact, sahaja samadhi, or spontaneous samadhi, is the best and highest meditation. Wherever you look, you see not only things but the spirit that animates them. Because we do not always understand this, we close our eyes for a while. To see the Self in stones, trees, and space is the meditation of the high ones. Whatever and wherever you see, you see God. Whatever you eat and drink is an offering to Him. Whatever you speak is His mantra. It is the Self that is eating, drinking, and seeing. The Self is in the self. O supreme conscious Rudra (a name synonymous with Shiva), you are man and woman. I bow to you. Rudra is sun, Rudra is light, Rudra is all. You should see the same within and without. If you have seen within, then the same will appear outside also. Baba Muktananda, Darshan magazine, #129 December 1997.

*

See Your Life As A Ritual

From the standpoint of the sages and the scriptures, one's entire life is a ritual. Even the smallest private events are rituals. For Baba Muktananda and all the great poet-saints of India, every action had the power of the ancient rituals. They performed every single action as a worship of God.

The Shiva Sutras say: "As above, so below. As here, so elsewhere." (3:14)

This great understanding enables a person to live his life as an offering . . . [to realize] that he is a reflection of the Divine . . . The Hindu faith also considers the entire universe as a place for divine worship. One of the most outstanding aspects of this form of awareness is that your own body, your very self, is an essential part of the ritual. You cannot remain separate from the worship itself. . . Your entire body must become a temple . . . the place where the deity abides. . .

The whole purpose of your life is to experience oneness with the Truth. For this experience to become constant, a divine attitude must be cultivated. And the best way to do that is to see your life as a ritual.

There is no separation, really, between sacred acts and daily activities. . . The Indian scriptures say, be vigilant: God dwells in every action that you perform.

Understand that a yajna [fire ritual] actually is going inside yourself. Your entire being is the yajna pit, and the fire in this pit is the Almighty. When your eyes perceive a yajna, may your gaze be turned within. This is the state, as Baba always said, that you must live in--the sambhava mudra, where even though the eyes are looking outside, the gaze is turned within. The mind is still . . . the breaths have become quiet. This is the shambhavi mudra where you are able to roam in the inner state of Consciousness, in the space of Consciousness within. Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, Darshan magazine, #129 December 1997.

The Shiva Sutras say: "As above, so below. As here, so elsewhere." (3:14)

This great understanding enables a person to live his life as an offering . . . [to realize] that he is a reflection of the Divine . . . The Hindu faith also considers the entire universe as a place for divine worship. One of the most outstanding aspects of this form of awareness is that your own body, your very self, is an essential part of the ritual. You cannot remain separate from the worship itself. . . Your entire body must become a temple . . . the place where the deity abides. . .

The whole purpose of your life is to experience oneness with the Truth. For this experience to become constant, a divine attitude must be cultivated. And the best way to do that is to see your life as a ritual.

There is no separation, really, between sacred acts and daily activities. . . The Indian scriptures say, be vigilant: God dwells in every action that you perform.

Understand that a yajna [fire ritual] actually is going inside yourself. Your entire being is the yajna pit, and the fire in this pit is the Almighty. When your eyes perceive a yajna, may your gaze be turned within. This is the state, as Baba always said, that you must live in--the sambhava mudra, where even though the eyes are looking outside, the gaze is turned within. The mind is still . . . the breaths have become quiet. This is the shambhavi mudra where you are able to roam in the inner state of Consciousness, in the space of Consciousness within. Gurumayi Chidvilasananda, Darshan magazine, #129 December 1997.

* * *

This part 2 of the Photography and Yoga project was

was announced in the "Latest Addition" section

of my website's Welcome Page on

June 29, 2015

Click on the images to enlarge

Photography and Yoga

Addendum : The Blue Peal

: